A brief reminder of this physiological phenomenon is necessary for a full understanding of the echocardiographic anomalies observed in ACP.

Normally, the right and left ventricles contract at the same time, during systole. When right ventricular ejection is hindered, as in ACP, right ventricular contraction is prolonged, whereas contraction of the left ventricle (LV) has already started its diastolic phase. The persistent pressure of the RV then reverses the transseptal pressure gradient, the pressure acting on the right ventricular face exceeding that on the left ventricular face. This pushes the septum to the left, as seen in ACP at the start of diastole.

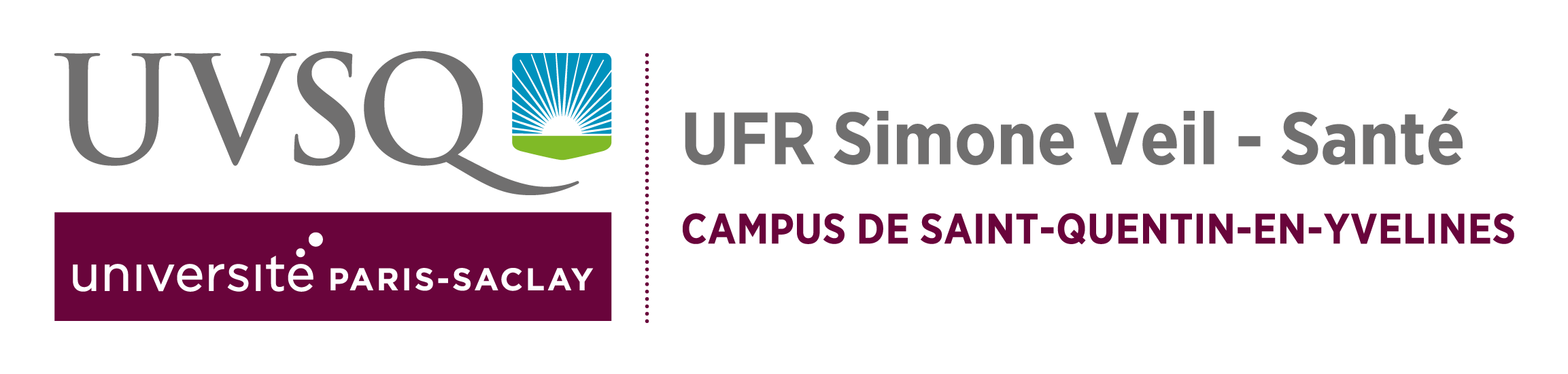

This septal flattening persists throughout diastole, since the right ventricular filling pressure is greater, because of diastolic overload (fig. 1). But at the beginning of systole, the transseptal pressure gradient is again reversed, and the septum is pushed towards the right ventricular chamber (Figure1).

This results in the “paradoxical” movement of the interventricular septum.

This septal flattening persists throughout diastole, since the right ventricular filling pressure is greater, because of diastolic overload (Figure 1).

But at the beginning of systole, the transseptal pressure gradient is again reversed, and the septum is pushed towards the right ventricular chambe (Figure 1). This results in the “paradoxical” movement of the interventricular septum.

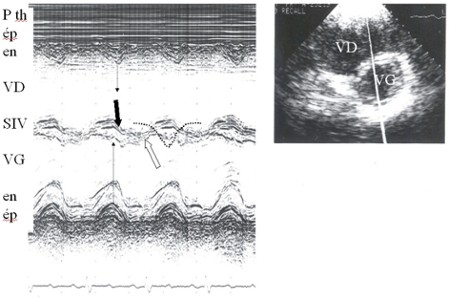

Another important physiological feature to take into account is the rigidity of the pericardium surrounding the two ventricles. Any right ventricular dilatation occurs at the expense of the left ventricle, which is compressed (Figure 2).

A final physiological parameter to recall is that right ventricular size varies with the quality of its filling: hypovolemia can markedly reduce the dimensions of the right ventricular chamber, and this disorder must be corrected before the echocardiographic examination if the results are to be interpreted correctly. Insufficient venous return affecting right ventricular size can be detected by ultrasound examination of the vena cavae (2, 3, 4). In particular, in a ventilated patient, partial or complete collapse of the superior vena cava on mechanical insufflation indicates hypovolemia.

Film 1 : Transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) longitudinal view of the superior vena cava (SVC) in a patient mechanically ventilated because of sepsis caused by lung disease. Two-dimensional imaging (on the right) coupled to M-mode (on the left) reveals collapse of the SVC on each insufflation. This image is suggestive of hypovolemia and indicates the need for volume expansion.

Film 2 : In the same patient as in film 1, volume expansion has corrected the circulatory insufficiency and eliminated SVC collapse on insufflation.